Chez Panisse was really all I dreamed it would be. Cozy, utterly welcoming, full of delightful culinary surprises. I went with my brother, sister-in-law, and boyfriend last Monday night, after exploring Berkeley for the day.

Coming into the restaurant, I was overwhelmed with an elated anticipation. It’s hard not to sound trite, but I really had the feeling I was entering some uniquely wonderful realm. The first-floor restaurant in Chez Panisse’s converted house has rich chocolate beams, simple wooden chairs, comfy booths, soft, warm light, and a generous view into the kitchen. The kitchen looked like the loveliest place on earth. Elegantly worn furniture and counters, calm and attractive chefs, an aura of easy happiness. Perfect.

We were each presented with beautifully printed take-home menus with that date’s unique first course, entrée, and dessert. It was the first time I’d been in a restaurant where you are entirely vulnerable to the chef’s judgment. I am anxious about the idea in general, being a notoriously picky eater with an abnormal sensitivity to spiciness. And yet I wasn’t especially apprehensive about the menu at Chez Panisse. I think I’d practically convinced myself that foods I couldn’t stand elsewhere I would eat here with relish.

First course: Leeks vinaigrette with shaved porcini and Parmesan. This was my favorite dish of the night, probably because it was also the one I was most nervous about. I hate onions and was worried about the oniony taste of the leeks, but in the very tart vinaigrette it was severely muted. In fact, the leeks tasted almost creamy. The Parmesan was stiff and sharp, and the porcini were extra acidic. It was so wonderful that no one spoke for several minutes because of our sensory distraction. Putting energy into talking at that moment felt kind of absurd.

Entrée: Canard aux olives – Liberty duck leg braised in white wine with green olives, ratatouille and soft polenta. This was a very homey, comforting meal. Really good, but not particularly exceptional. The duck was crispy and delicious. The olives were the second case that night of a delicate acidic flavor tasting creamy, and it was delightful. There was jus all around, making for a thoroughly enjoyable dish. I found out later, while reading Thomas McNamee’s Alice Waters and Chez Panisse, that canard aux olives was also the main course served on opening night in 1971!

Dessert: Black Mission fig tart with Sauternes Sabayon. I’m not a big fig fan, but I loved this. The figs had an alcoholic, kind of burnt taste which was terrific. Definitely added a complexity to the fig flavor, which I think tends to be boring. But the real genius of the tart was the crust–wow! It was incredibly flakey. The bottom layer of the crust had barely let any fig juice soak into it, and it flaked apart in your mouth. It was also sugary and very tasty, unlike lots of bland crusts I’ve sampled. I’ve only baked one tart so far (which was, in fact, from the Chez Panisse Desserts cookbook) and my crust turned out nothing like this. Something to aspire to! The Sauternes Sabayon was a very nice accompaniment–a barely sweet, thick whipped cream. The flavor of the Sauternes complimented the alcoholic taste of the figs very nicely.

However, despite all this gastronomic elation, something happened at the start of the second course that drastically altered the meal for me. I’d intended to take some pictures of my food that night, primarily with this blog in mind. The first course was so surprising and enticing that I had forgotten about picture-taking until I was halfway through, and then reasoned the main course might be more appropriate anyways. After the beautiful plate of duck arrived, I fished my phone out of my purse as inconspicuously as I could. I thought I would even pretend to be checking my email or something to appear less noticeable. At this exact moment of mimed casualness, I became aware that a guy at the table next to us was talking about me. He was about my age, there with his girlfriend, both of them dressed in an expensive preppy way. They also apparently knew much of the Chez Panisse staff and dined there often. He was saying, “Wow, those people are taking pictures of their food. I mean, they could be doing something else on their phone but it looks like they’re taking a picture.” What? My heart was beating fast. He went on to say how ridiculous it was, how I obviously didn’t appreciate the food, being primarily interested in taking a picture like some tourist. His commentary was loaded with the judgment that here was this ignorant, tactless person for whom the whole Chez Panisse experience was a novelty, who could never understand the caliber of the food. I think he even made an overtly classist remark, like, “You or I would never take a picture of our food.”

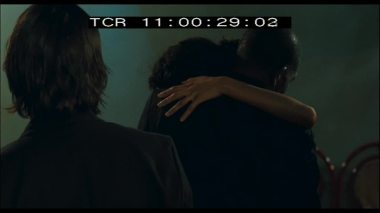

I felt so scared and shamed that I copped out altogether, finishing my actions on the phone as if I really had been looking at an email, and started to eat my duck with shaking hands. Aaron saw that I hadn’t taken a picture and sensed something was wrong, and quickly took his own picture of me and my food. He didn’t get much of the food in there, mostly my nervous smile, but he did capture the jerky guy in question in the background (which gave us a good laugh later).

I couldn’t believe how expertly they had preyed upon my exact anxiety. I had thought I might attract a disapproving look, maybe, at the most, but never anticipated this attempt at humiliation. Being the intensely sensitive person I am, I felt shamed to the point of tears and dropped out of table conversation almost completely as I struggled to concentrate on my food. What especially saddened me was that this attitude was so out of step with the philosophy of Chez Panisse. Alice Waters intended it to be the most unpretentious of restaurants, where even the food would play second fiddle to warm conversation in a homey atmosphere. How was it that these people had appropriated it and made it an elitist, exclusive place? I guess it’s inevitable that a restaurant that great, no matter how informal its intentions, must end up cultivating a snobbishness about it from a certain portion of their clientele. I did notice that the wait staff agilely and subtly adjusted their behavior to give off a “one of you” vibe to the preppy table and a few others, without losing the general friendliness and openness that had established such a nice feeling in the dining room.

I was extremely frustrated, in the moment and long afterward, as I viewed myself from the outside. I happen to be a financially stable young woman who’s been fortunate enough to do a lot of traveling and can indulge in extravagance every so often. But what if I wasn’t financially stable, and had been saving up for this meal for a long time? Anticipating it for months in advance, my chance to try this fabled divine food? And what if, finally on that special night, I overheard such brutal, wounding comments? Or to go down another speculative path, what if I had been taking a picture for a loved one physically or financially unable to come to the restaurant, but who wanted to share in the joy of my experience?

This capacity for cruelty, simply to reaffirm the couple’s own superior positions, was so frightening to me. All the implications of their behavior shook me up for the rest of the night, until I was back in the car with my family and we could laugh at the ridiculousness of the whole thing. Of course I shouldn’t care about such small-minded opinions. Of course those people are laughably irrelevant to me. I thought then that maybe I could let it all pass without too much further worry. But after the contained safety of the car, being alone with my own mind, I knew I couldn’t forget it. Thoughts of how I could have and should have responded to those comments began to plague me. I’d focus on another topic and then suddenly be dreaming up deliciously mean retorts without even realizing it. I am forever cursed to let the moment of engagement pass irrevocably in these types of situations before I can figure out how to answer. I become so flustered physically and so unsure of whether my internal pain deserves to be voiced that I say nothing. It’s only long after that I realize all the things I should have said. I torment myself by playing the scenario over and over in my mind, vowing to keep an arsenal of verbal self-defense at the ready for next time.

What the experience most made me think about was the capacity for everyday cruelty that strangers have towards other strangers, and how some people are totally able to deflect this cruelty, and others (like me) absorb it and agonize over it, falling into a deep pessimism about human nature. This is a big problem for me living in New York. The subway is a regular source of pain for me, a minefield of injurious moments, both received and given. (I too participate in moments of anonymous brutality, the effects of group mentality boring into me, and it’s disgusting.) I keep reasoning that I just need to move away from the city, but I’m not really sure that would change much. I feel I should work on becoming less sensitive, but I also don’t see that as my responsibility.

injurious